This week, we have a breach involving exposed API keys for payment integration, leaked API tokens on Travis CI, the shortcomings of static and dynamic application security testing (SAST/DAST) for API security, and the value that API specification frameworks bring.

Breach: Exposed payment integration API keys

The big news story this week was the leakage of API keys for payment integrations that potentially exposed transaction details and personally identifiable information (PII) of millions of users.

CloudSEK, the maker of artificial intelligence-enabled digital threat protection, revealed that many mobile applications have API keys hard-coded into the application packages. This is security by obfuscation, because a hacker could easily recover such tokens, using just basic reverse engineering skills.

Indeed, the researchers at CloudSEK discovered that of the 13 000 applications currently uploaded to their BeVigil site, approximately 250 used the Razorpay API to enable financial transactions — the most critical information since it pertains directly to users’ financial details and PII.

Most worryingly, CloudSEK found that ten applications using the RazorPay API appeared to be exposing their integration key ID and secret. The impact of such exposure includes the possibility for a rogue actor doing the following:

- Query payment information

- Revoke unauthorized transactions

- Access PII details (like phone numbers and email addresses), transaction details, order and refund details

The researchers suggest that such key exposure could allow attackers to issue high-value refunds for items purchased, or sell the details on the dark web.

Lessons learned here include:

- Being reliant on security by obscurity (here “hiding” API keys in an application package) is no substitute for robust security controls. In this case, it is the equivalent of locking a house door and leaving the key under the doormat.

- Application developers should anticipate that sensitive API keys and tokens may be exposed during an application’s lifecycle and should have robust, repeatable mechanisms in place for revoking and recycling exposed credentials.

- Sensitive credentials should never be committed into version control systems — we discuss this below in more detail.

Breach: Leaked API tokens on Travis CI

The other big news this week was the breach at the popular CI SaaS platform, Travis CI. They have acknowledged the breach, but sought to downplay its significance in a post on their community forum.

The breach was significant in terms of both the scope and the potential impact: by forking a public repository and then issuing a pull request, attackers could gain access to the entire environment of the upstream repository, including all secret values like API keys and tokens. Such credentials would typically be used for access to downstream infrastructure environments, such a cloud hosting and binary repositories. A compromise of such API tokens could quite easily poison entire software supply chains. We all still remember SolarWinds, right?

Travis CI stated that they had resolved the underlying problem with a series of security patches, and suggested that users change passwords and rotate tokens and keys. As further mitigation, they noted that this vulnerability applied only to public repositories, although in practice these are simply the ones most likely to be forked at scale.

The security industry was somewhat critical of this response. A member of the security research team at Etherium, Péter Szilágyi, was critical of Travis CI, in particular on their incident response, stating:

“No analysis, no security report, no post-mortem, not warning any of their users that their secrets might have been stolen“.

Furthermore, the renowned malware researcher Jake Williams concluded that they were “guilty of an abysmal failure in handling an extremely serious vulnerability”.

The key lesson here for users and API consumers is that API tokens and keys are valuable assets, particularly when they govern access to your downstream supply chain. Unfortunately, as this Travis CI incident reveals, the token or key owner is at the mercy of 3rd party platforms for the secure storage and use of said tokens. Best practice would be to assume that a total disclosure of all API tokens and keys is a possibility and set in place a well-rehearsed procedure for the revoking and re-issuing them.

Opinion: SAST/DAST shortcomings for API security testing

I was pleased to be featured in the NewStack this week, discussing the pros and cons of the stalwarts of Application Security (AppSec) testing — namely SAST and DAST — for the security testing of APIs.

My view is that most organizations will be running some form of AppSec program, nearly always deploying SAST and in most cases some form of DAST too. As organizations increasingly adopt APIs, the discerning AppSec manager is posed with a question if the existing tools are adequate for the task of API security testing, or whether they should be supplemented with more specialist tools. My conclusion is that the best approach is to complement your existing test regime with specialist tools that give more insight and context into API-specific security issues.

Based on over a decade’s experience using and developing SAST/DAST tools, my view is that fundamentally these tools lack the context required to accurately detect many API security issues. In the case of SAST, these tools were designed to work with web pages built, for example, on Java Servlet Pages or .Net ASP pages. Such tools may not be able to adequately recognize API ingress points — like function decorators in a Python Flask API application — and as such are unable to construct a sufficiently accurate model for analysis.

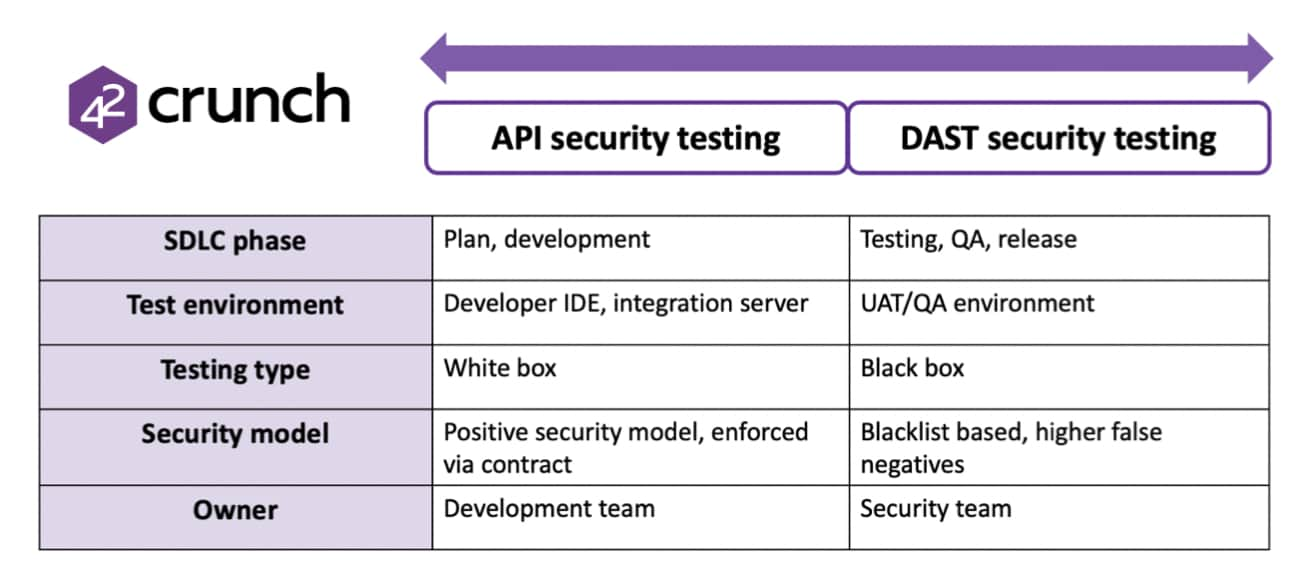

DAST also lacks context when analyzing APIs, because the technology is typically expecting a website and will “spider” the site to find entry points, such as forms that can be attacked or fuzzed. Many DAST tools lack the ability to enumerate REST API endpoints, meaning that large gaps may exist in their coverage. Additionally, DAST is typically performed later in the development lifecycle because they require a largely functional application to assess, whereas API-specific test tools can be deployed in parallel to the initial development activity, thus allowing a hard “shift-left” approach. The differences are summarised below:

My conclusion is that SAST/DAST tools provide significant efficacy in reducing application vulnerabilities and that the addition of API-centric test tools into an existing AppSec program ensures that API coverage is even further improved. It’s a case of defense in depth.

Article: The value of API specification frameworks

Finally, this week we have an article on the value of API specification frameworks, such as the OpenAPI Specification (OAS), which allow organizations to drive both the quality and security aspects of their API development.

By using a central repository of APIs and a well-specified and open standard like the OAS, it is possible to define APIs in a language-agnostic and machine-consumable format that allows for the following:

- Automatically generate API “stub” functions for development activity

- Auto-generating mocking frameworks for integration and unit testing

- Test the conformance and performance of API implementations against the specified contract

- Automatically audit the security and quality of API definitions as they are developed and committed to version control

The author Sheryans Mehta concludes that although an API development approach centered on API specifications requires a commitment in time and effort, this is rewarded in the long run: “The reality is that shift left IS working, it IS catching flaws earlier.”

Get API Security news directly in your Inbox.

By clicking Subscribe you agree to our Data Policy